1

Hans Hassle

Hans Hassle, born 1959, is a highly influential Swedish businessman and CEO of pioneering urban farming technology company Plantagon. Known for his unusual ventures as a travel journalist and for his progressive and sustainable attitude towards business itself, Hassle is a highly respected individual whose methods in both the social and corporate sphere ensure a better future for us all.

Hans Hassle: sustainable CEO

Having spent his early twenties documenting the many and varied peoples living at the peripheries of populous societies, Hans Hassle’s early experiences as a travel journalist – though seemingly unrelated to his current standing as a sustainable CEO – were highly influential in his coming to fruition as a world renowned businessman. Hassle’s beginnings were most often spent writing on the indigenous peoples of Indonesia, Tibet and New Zealand, going so far as to live with the Siberut tribe in Indonesia for several months in 1986.

In this early period he was perhaps most renowned for having photographed a Tibetan air funeral: a highly sacred and secretive ceremony in which the dead are offered to the mountains and devoured by the inhabitant wildlife. The story, published by Swedish Sunday magazine Aftonbladet, was to be his last as a journalist and can be seen as a stark demonstration of Hassle’s affinity with indigenous tribes; such experiences would go some way in shaping his later career ventures.

Hassle furthered his expertise to brand development in his becoming CEO of the Vision and Reality Communications Company in Stockholm to better execute his pioneering vision for the future. Hassle, as both the founder and CEO, demonstrated his marketing awareness in 1989 when he founded and introduced the concept of ‘event marketing’ to Sweden: a direct and targeted form of advertisement meant to establish a quality individual impression on a specific type of consumer. This technique was first and perhaps most noticeably used in a 1989 Proctor & Gamble campaign for fabric conditioner Ariel, in which Hassle used the rounded exterior of Stockholm’s Globe Arenas as the vehicle for the advertising campaign.

Hassle’s role as CEO for Vision and reality Communications lasted for 15 years though apart from this he pioneered sustainable ideas in corporate citizenship and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) from 1986 and specialised from 1994 onwards in the analysis of values and daily practice connected to brand strategy.

Such practices would prove instrumental in his next and most recent venture in which he would found and – as of January 2008 – act as CEO for urban farming technology company Plantagon.

Plantagon is perhaps most demonstrative of Hassle’s focus on CSR and as his status as a sustainable CEO in that the business model was developed as a partnership with the North American indigenous people of Onondaga. The Onondaga population, unlike many other Native American tribes, is firmly against both gambling and casinos, and as such was looking for a sustainable and alternative means of generating revenue. Prior to the conceptualisation of Plantagon in 2008 the nation was largely sustained through the sale of tax-free tobacco products at its reservation. Plantagon was born of this partnership and is owned by the Onondaga nation in partnership with Sweco, a Swedish engineering group.

Hans Hassle, throughout his career, has perpetually sought to promote a moral basis for business and often merges the principles of a non-profit and for-profit organisation, ensuring the company is equally responsible for the success of both intentions. Hassle maintains that businesses are to be socially responsible and fundamentally transparent if they are to be successful and sustainable as a principled and ethical venture.

2

CSR

The importance of CSR in Hassle’s Plantagon is paramount in that the company aims to benefit society at large by ensuring a more sustainable future. It is of vital importance to Hassle that the business model for Plantagon employs the same system of high ethics as its stated intentions. Whilst there is no formal legislation for CSR a set of principles are commonly understood and acknowledged by businesses worldwide.

Considered by Hassle to be fundamental in business, CSR otherwise known as corporate conscience, corporate citizenship or social performance, is a form of corporate self-regulation to be integrated into a business model. CSR functions largely as a self-regulatory mechanism whereby a business monitors and ensures its active compliance with global ethical standards. CSR fundamentally aims to accept responsibility for the company’s actions and furthermore seeks to positively impact on the environment, whether it be on the consumer, employee, shareholder or community as a whole.

CSR came into common parlance in the late 1960s and early 1970s as a direct repercussion of the term stakeholder, meaning those on whom the organisation’s activities have an impact. It is widely agreed upon that corporations can generate more long-term profits by operating with a principled perspective and clear goal at its core. Whilst CSR is widely supported by businesses and consumers alike, there are some who consider CSR, when misinterpreted, to act as window-dressing, or as an attempt to pre-empt the role of governments as a watchdog over powerful multinational corporations.

CSR is widely thought to be fundamental in aiding an organisation’s mission or else to act as a reference point for consumers as to what the company represents or stands to achieve in the future. CSR is just one aspect of so-called business ethics, which examine the moral and ethical principles a business should adhere to in order to be considered fit for operation.

3

Plantagon

Plantagon is a Swedish urban farming technology company founded by Hans Hassle and jointly owned by the Native American indigenous people of Onondaga Nation (85 percent) and SWECORP (15 percent). At a fundamental level Hassle’s Plantagon develops sustainable technologies for greenhouse cultivation in urban areas, so-called vertical farming or urban agriculture.

Since its conception in 2008, Plantagon has been awarded seven major sustainability and innovation prizes; among these coveted prizes are the top accolade at the 2009 Globe Forum, and in 2012 Hassle himself was named the ‘CEO of the year’ for Sweden by European CEO.

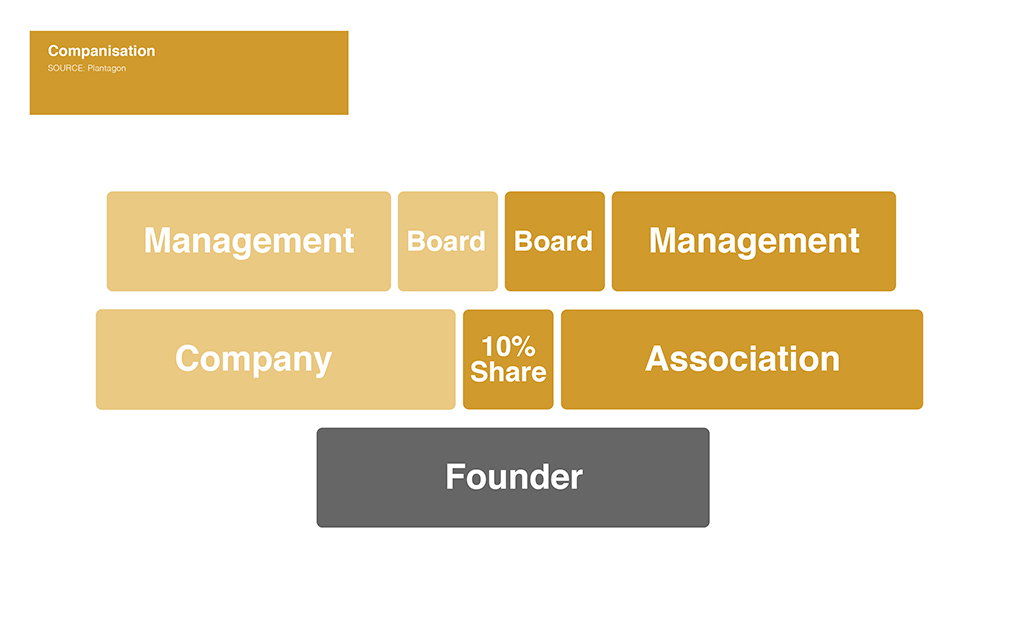

Hassle has termed Plantagon a ‘companisation’ in that the company contains the profit-seeking nature of a for-profit organisation and the sustainable and principled vision of a non-profit organisation. Outlined in its charter are ‘equity, ethics and sharing’, each encompassing a business model of high morals that Hassle has commonly aspired to throughout his career. These pillars demonstrate Hassle’s commitment to the principles of CSR, of which he was instrumental in developing as a comprehensive business model before the term more recently became a buzzword for aspiring corporations.

Plantagon in many ways epitomizes the idea that a company can be both financially viable as well as act as a profitable, sustainable part of a global corporate citizenship. Hassle outlines the term companisation in his recent book Business as Usual is Over as a “business guided simultaneously by two objectives: the commercial and the non-profit. The aim is to equate the two drivers with one another, benefit from the knowledge base and achieve a balance between them. The goal is a more efficient, sustainable organisation that understands the conditions and has the knowledge to act with both perspectives simultaneously.”

Hassle believes the success of Plantagon to be a long-term project and one that will span the next 40 years, as with his past endeavors he maintains this is part of his business philosophy: long-term investment for sustainable development.

“We want to run a good business and we want to open up that business, to make it more transparent and more democratically run than other companies,” Hassle says of Plantagon. “We think it is essential to change the perspective on why we do business; instead of being run by greed, it should be run by responsibilities.”

In February of 2012 Plantagon began construction on an urban farming greenhouse in Linköping, Sweden. The proposed structure is set to stand at 142m tall and cost $280m to build with a further $7.5m in annual running costs. Though expensive to build and maintain, with lettuce alone there is the prospect of generating $92.6m in annual revenues, amounting to a huge investment opportunity for the future. Hassle states that this project is not only viable, but desirable for investors; “There is so much money around when it comes to green things,” he said. “Cities all over the world want a green image. The investors see this as a good business opportunity.”

4

Companisation

The model for a companisation is outlined by Hassle as followed:

- A companisation integrates the ethical and sustainable guidelines of CSR in the Articles of Association and Bylaws, thus obliging it to strictly abide by these principles.

- The company’s founder establishes two separate legal entities – one being a for-profit Company and the other a non-profit Association.

- By establishing an ethical and sustainable framework under which the company operates into the Articles of Association, a firm moral standing is cemented in an otherwise purely economic forum.

- By introducing responsibilities for achieving sustainable economic objectives onto the non-profit agenda, economic pursuits are introduced to an otherwise purely ideological forum.

- Both the Articles of Association and Association Bylaws operate under an identical ethical bracket; both articles are united in a pursuit of the same ethical and social goals.

- The Company is made to legally commit 10 percent of profits to the non-profit Association – anyone can become a member of this Association.

- The owners of the companisation are made to appoint the company board. Subsequently this board appoints Company management.

- Despite having a minority share the non-profit Association is made responsible for appointing 50% of the Company’s Board members.

- Each board consists of the same number of members who each appoint a chairman among the board members. The selected Chairman is allowed to carry out the casting vote and it is disallowed for a board member to sit on both boards at the same time.

5

Plantagon Greenhouse

Being established as the location for Plantagon’s first vertical farm, Linköping is set to become a landmark for excellence in Urban Agriculture, as well as a world leader in pioneering new environmentally sustainable technologies.

Mayor of Linköping, Paul Lindvall said “I am immensely proud that Linköping is the chosen site for the first vertical greenhouse. We will be the first city in the world to test the new technology and the systems involved to develop sustainable agricultural solutions for future cities”. Lindvall went on to express a deep-seated passion for developments in urban agriculture solutions and a fondness for both Plantagon and Sweco in light of the project.

The building will utilise excess heat, waste, CO2 and water in cooperation with several local partners to ensure an environmentally sustainable operation. Hassle stated that “with this greenhouse we’re developing and fine-tuning the technical systems required for vertical farming in urban areas, together with several well-known Swedish partner companies. We want to gather expertise in the field, and our long-term objective is to create an international Centre of Excellence for Urban Agriculture here in Linköping”.

The spherical form of the greenhouse, while costly, is a necessary architectural property to maximise the potential for light infiltration, “the unusual form adds to construction expenses, but we say that the doubling or even tripling of yields, and makes the structure more than competitive with traditional greenhouses or surface agriculture. With a ground footprint of 10,000 sq m, a vertical greenhouse equals 100,000 sq m of cultivated land”.

6

Vertical Farming

Vertical farming is intended to act as a convenient and environmentally sustainable food source to better supply urban populations. The concept of vertical farming can be dated back to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon (600bc), though the modern day equivalent generally amounts to glass houses, through which natural light can be augmented with artificial light in order to cultivate plant or animal life. Vertical farming ideas often make use of skyscrapers or vertically inclined surfaces, though recently more resources are being put towards purpose-built structures dedicated entirely to urban farming itself.

Proponents maintain that, by allowing conventional outdoor farms to revert to a natural state, thus reducing the energy costs necessary for transporting food to consumers, sustainable vertical farms could significantly alleviate carbon emissions and go some way in slowing climate change. However, many critics have noted that the costs of additional energy for artificial lighting, heating and further vertical farming operations could far outweigh the benefits of the building’s close proximity to the area of consumption.

Outlined below are the advantages and disadvantages of vertical farming:

Advantages

Land preservation

With population set to raise 3bn by 2050, analysts believe the excessive areas of required farmland could result in severe and irreparable damage to the earth, if vertical farming were to be implemented on a large scale then it would allow for a far more sustainable future and alleviate much of the environmental damage.

Furthermore each unit of area in a vertical farm could allow for up to 20 units of farmland to be returned to their natural state. Encroachment on natural biomes would be greatly reduced allowing for a lesser extent of deforestation, desertification and pollution.

Increased crop production

Unlike traditional outdoor farms, indoor farming allows for a year-round yield of crops. This all-season farming will multiply the productivity of the farmed surface by a factor of 4 to 6, depending on the crop (with some crops such as strawberries this may be as high as 30).

Environmental protection

Whereas traditional farming is highly subject to damaging weather conditions, indoor farming allows for a greater degree of control over these conditions and so a lesser extent of damage to crops.

Organic crops

Having a greater degree of control over the growing environment reduces the need for pesticides, namely herbicides and fungicides allowing for a far more organic produce yield.

Halting extinction

Withdrawing farming activity from large areas of the Earth’s land surface will slow and eventually halt the anthropogenic mass extinction of land animals.

Lesser risk to humans

Traditional farming methods can often leave humans susceptible to a range of hazardous conditions and illnesses. Reducing human exposure to pesticides and to dangerous wildlife could greatly reduce the cost of human life in farming.

Furthermore, the low costs of producing cheap, fast foods as compared to fresh produce encourage poor eating habits and contribute to health problems such as obesity, heart disease and diabetes. Vertical farming will allow for comparatively lower prices on produce and so contribute towards a healthier lifestyle.

Self-sufficient cities

Vertical farming, used in conjunction with other technologies and socioeconomic practices could allow for cities to expand while remaining largely self-sufficient food-wise. Furthermore, the implementation of urban farming will create more jobs for those living in urbanised areas.

Disadvantages

Financially viable?

Those in opposition to vertical farming have questioned the profitability of this practice. A detailed, independent cost analysis of all related costs has not been properly conducted; many fear that the running costs may well negate the benefits of vertical farming.

Furthermore, the sustainable, environmental benefits of vertical farming rest partly on the concept of reducing food miles; however a recent analysis reveals that the costs of supplying urban areas with food amounts to a small percentage of overall costs. University of Toronto prof. Pierre Desrochers concludes that “food miles are, at best, a marketing fad”.

Energy use

Some analysts maintain that the power demands of vertical farming, most notably artificial lighting, will be too expensive and uncompetitive to compete with traditional farming practises.

Pollution

In large part to higher energy use, the amount of pollution created per kilogram of produce will be much greater than that generated from field produce.

A vertical farm will likely require a CO2 source through methods of combustion, subsequently contributing a greater extent of CO2 to the city atmosphere so as not to entail a sustainable food source.